No sooner had the recent draft India-US trade agreement been made public than it was met with outcries from the Indian commentariat. The biggest bone of contention was the US requirement that India phase out its oil imports from Russia. These had risen from 2% of total oil imports in 2021 to 36% by 2024, reflecting the massive discount on Russian oil – about US$35 per barrel below Brent – following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

In fact, with the discount declining to about US$2 recently, oil imports from Russia have fallen accordingly. But controversies over the provenance of oil imports ( be they from Russia, Iran or Venezuela ) are likely to continue, calling attention to the deeper, underlying problem afflicting India’s economy: energy dependence.

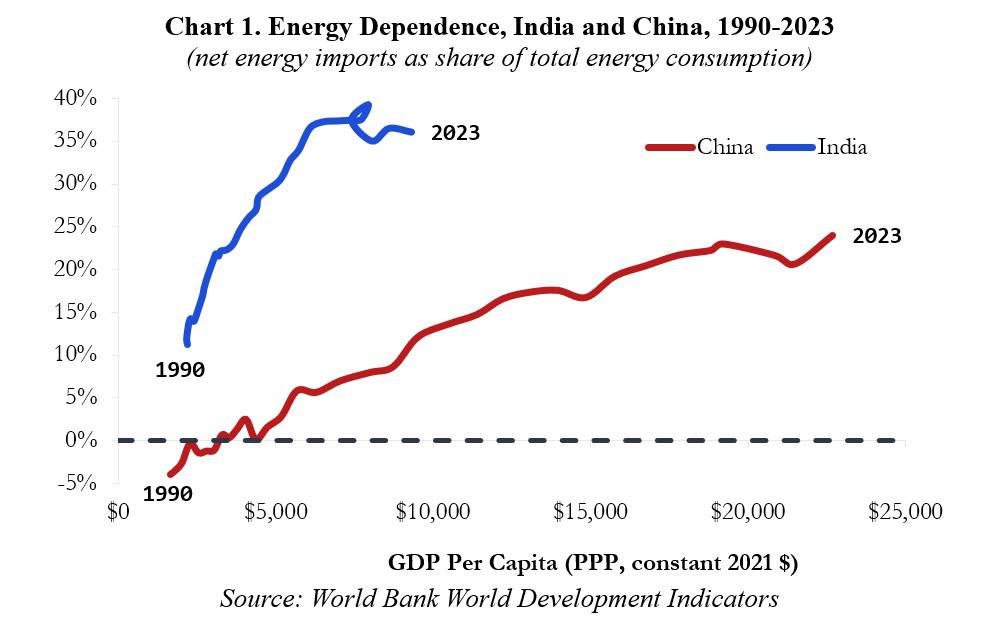

Consider energy imports as a share of total energy consumption for India and China over the course of their recent economic history ( Chart 1 ). Not only is India heavily dependent on imported energy, but its dependency has risen from 10% of energy consumption in 1990 to over 35% in 2023. By contrast, while China has also been quite energy dependent, it has been much less dependent than India at comparable points in its development.

The upshot is that economic dynamism and growing prosperity have made India more, not less, dependent on imported energy. But now that geopolitical wrangling increasingly shapes international trade, India must reduce this dependence to maximize its strategic autonomy.

One option would be to invest more in hydrocarbons, as the United States under President Donald Trump has done. But another option is to embrace the Chinese approach and become a renewables-based electro-state. This has many advantages. The sun and wind are available to most countries, and they are especially strong in India. Drawing more on these sources would not only reduce dependence but also drive electrification, which is key to sustaining the industries and technologies of the future: data centres, electric vehicles, drones, artificial intelligence ( AI ) and so forth.

Moreover, India has two other compelling reasons for shifting strategically from hydrocarbons toward renewables-based electricity. The first is pollution. The domestic social costs of burning coal and oil have been devastating, as a recent World Bank study demonstrates. New Delhi, an “open-air gas chamber”, is a grim reminder of the consequences of doubling down on hydrocarbons. Thus, a shift to using more coal is inadvisable, even leaving aside the fact that US$40 billion to US$60 billion in thermal power investments are already stranded or at risk, and that new plants will only add to this burden as solar-plus-batteries outcompetes coal.

To be sure, the move to renewables does risk trading oil dependence for technology dependence, since China controls over 80% of solar manufacturing and dominates battery supply chains. But that brings us to the second reason to make the shift: cheaper electricity will be crucial to seizing India’s last opportunity to revive manufacturing. In A Sixth of Humanity: Independent India’s Development Odyssey, Devesh Kapur and one of us ( Subramanian ) show that manufacturing has been hampered by electricity costs that have been twice as high as they should be, and double those found in competitor countries.

In fact, India’s information-technology revolution holds up a mirror to the manufacturing failure: reforms implemented in the telecommunications sector positioned it for success, while a lack of reform in the electricity sector did the opposite. Fortunately, the recent trade agreements that India has negotiated with the European Union and the US could give it a chance to exploit the “China+1 opportunity” ( multinationals’ diversification of production beyond China ). Realizing this opportunity, however, will require domestic reforms, especially in the power sector.

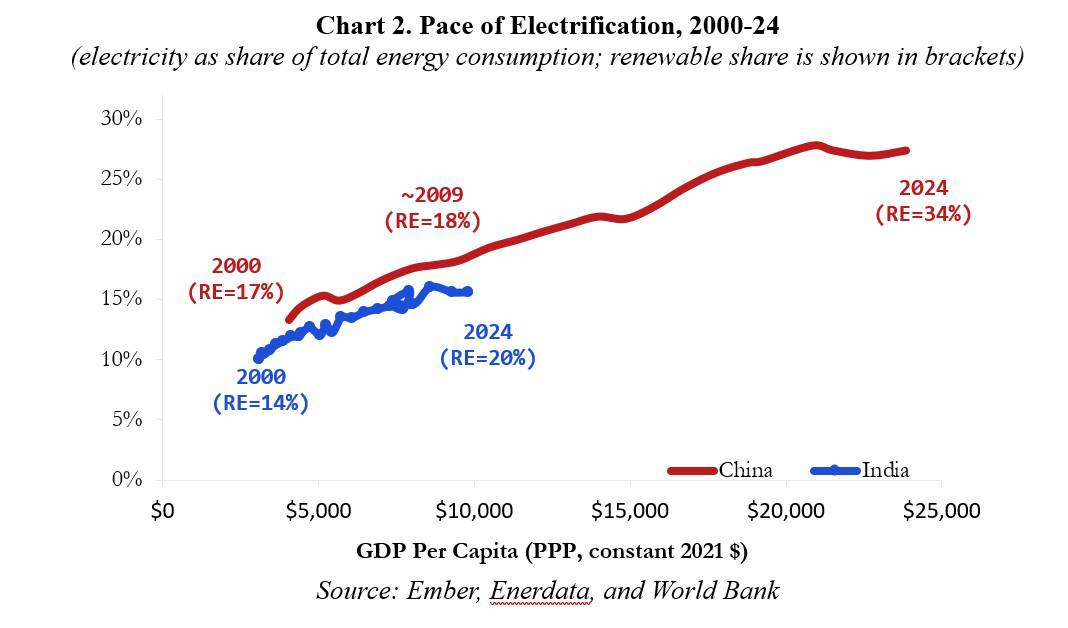

With electricity accounting for 15.6% of total energy consumption ( Chart 2 ), India’s electrification share is below what China’s was at a comparable level of development ( in 2009 ), and well below where China is today ( 27.4% ). Similarly, Chinese renewables as a share of the total are higher, at 35% compared to 20%. India is thus far behind China in its quest for energy independence.

The recent triumphalism about India leapfrogging China is premature. Its rising renewable share owes more to the 90% fall in global solar costs since 2010 than to anything else.

India’s governmental and industry commitments to renewables are undeniable, and it has added renewable capacity at a brisk pace, including 50 gigawatts ( GW ) in 2025. Its potential for solar and wind is well-established, and its green hydrogen auctions have fetched globally competitive prices. But serious structural and institutional problems threaten to stymie progress. The most important is the fragmentation of decision-making and governance across the central government and each of the 28 state governments, with the latter controlling the critical distribution sector.

As mostly public sector monopolies, Indian distribution companies ( “discoms” ) are chronically in financial straits, owing to populist political pressures that keep prices well below cost. After operating at a loss for many years, discoms overall have accumulated roughly US$75 billion in debt.

As a result, they have been unable to buy power from renewable generators, which in turn have over 50GW of excess supply. They also are poorly positioned to ramp up investment in the grid and storage systems ( US$50 billion is needed by 2035 ) without which India cannot possibly become an electro-state. Currently, some 60GW of power is impeded by inadequate transmission capacity.

If India is going to overcome its energy dependence, it must accelerate its transformation into an electro-state – starting immediately. The central government is moving in the right direction, but much bolder reforms are required, especially on the part of state governments. The dominance of inefficient, poorly managed public sector monopolies must be addressed. Fostering competition and creating rival institutions that are nimble enough to facilitate the technology transition will be essential. The slower India goes, the more vulnerable it will be to shifting geopolitics of energy.

Navneeraj Sharma is an energy economist and Arvind Subramanian is a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Copyright: Project Syndicate